30 Nov 2025

Who we can help: How can I help the next generation without ruining them?

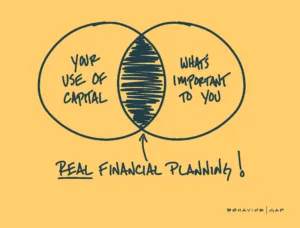

One of the questions I have from clients is around passing on wealth from grandparents to grandchildren, or from parents to children. And the most common concern is how to achieve something that is financially astute, and part of every family’s instinct to help their own, without causing more harm than good for the recipient.

One grandmother confided to me, “I trust my grand-daughter, she’s growing up as a good, normal kid. But what if she reaches 18 and has an idiot boyfriend who convinces her to spend money she’s inherited from me on frivolous things?”

In jest, I considered replying that my wife has had an idiot husband for many years but so far she’s not been swayed! 😄

In reality, it’s a common concern that age 18 may be too young for many people to act responsibly with any significant sum of money. Legally a Junior ISA does belong entirely to a child when they turn 18 years old and they can take whatever decisions they want with it. But there are several informal as well as formal ways to moderate this.

First, many families use a trusted financial planner because this means that their children can begin to receive some financial advice and education as part of a wider family relationship. In many ways, a smaller investment is an ideal starting point for a young person to begin to understand the many different aspects that need to be considered when investing – including time frames for investment, as well as investment risk decisions and their implications for the potential future value of an investment (investments really can and do go down as well as up in value).

Second, it is not uncommon for parents to ask their child to continue to keep them informed about money which was received from them or their grandparents. In fact, the child may not wish at this stage to be very involved. Fear of the responsibility of making decisions over money is not an uncommon early reaction. In which case, a young person may be very grateful to have the continued support and guidance of their parents, together with their financial planner, as they start the journey towards taking adult responsibility for money.

Third, there are other more formal ways to resolve concerns about irresponsible behaviour, by gifting money in forms that are less immediately accessible for someone who may still be too young. Trusts continue to be a popular way of protecting young people from themselves, although they do carry additional costs to set-up and are subject to slightly different taxes, which trustees need to be mindful of.

An idiot husband rather than boyfriend is a slightly knottier problem – especially if people get married young. But in many cases, it is common now for a couple to sign a pre-nuptial agreement which ring-fences any capital brought into the marriage from being part of divorce – although growth in the capital value during the marriage is likely to be subject to any split.

Another grandfather was concerned, “I saw some of my friends’ grandsons who inherited money go and blow it all on a fast car. That money was supposed to help them buy a house.”

Here the real question is about what the family have done to actively shape values and discuss a shared culture around wealth and money. I’ve often likened talking about money to talking about sex, it’s not necessarily comfortable to do it, but frittering away hard earned family capital on a fast car is a bit like a teen pregnancy – it starts off as a short-term thrill but with long-term consequences.

Parents and grandparents have a moral responsibility to ensure that they impart not just capital, but also values and accumulated family wisdom to their descendants (see my article on different types of family capital in the Thinking section of this newsletter).

And importantly, moral authority is not just a soft power. Some of the wealthiest clients I have worked with not only cultivated in their children healthy attitudes to the value of money and hard work, but they also had no qualms about setting expectations for responsible behaviour. By gradually introducing the rising generation to sums of capital, and making it clear to recipients that if they were irresponsible with it, then future gifts or inheritance would not be forthcoming. Even an impetuous young person is likely to see the value of sensible behaviour if doing something rash means they risk being excluded thereafter from their grandparents’ or parents’ wills.

Fear is a natural emotion when making big decisions, but it should not be the over-riding one. I encountered a client who was in his 80s and had more than enough money to last him for the rest of his life – to the point where I was encouraging him to consider making a gift from his excess wealth to his 54-year old, divorced daughter, who was having a tough time.

He said, “I don’t want to affect her choices in life, it’s better that she gets things when I am dead”.

What I helped him to see, was that by not making any gift, he was affecting her choices: perpetuating the stress she was under of continuing to pay off her mortgage single-handedly. If she was freed from this, she would be in a position to make bigger pension contributions, and to build up her own savings to protect her in case of a change in her work or health. We know that reducing potential financial vulnerability can make a big difference to stress and overall quality of life.

In a situation like this, I’m often mindful of former Labour Chancellor Roy Jenkins’ description of inheritance tax as “a voluntary levy paid by those who distrust their heirs more than they dislike the Inland Revenue” (now known as HMRC). Most grandparents or parents have far more sway over their nearest and dearest than any of us do over what the government will do with taxes raised from all that you’ve worked hard to accumulate in your life.

The joy of making a real difference to the life of someone you care about, and of being a good provider for others, is not a small thing and we should not let this positive thing be overshadowed by fear.

Instead, carefully consider, with the help of an astute financial planner, the different options for gifting and how those gifts can be preserved or used by recipients, and then act to make a real difference. For more insight, download our free guide to Estate Planning (Footnote 1)

What is your plan to preserve your family’s capital across multiple generations?

If you’d like to discuss making a gift, or planning intergenerational wealth, please book a free initial chat here: https://calendly.com/duncan-bw-hoebridgewealth/30min

NOTE: None of the above is financial or investment advice and you should speak to me or someone else professionally qualified to give you advice specifically tailored to your circumstances. Thresholds, percentage rates and tax legislation may change in subsequent Finance Acts. The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate Wills, Tax and Estate planning.

FOOTNOTES

Production

Production